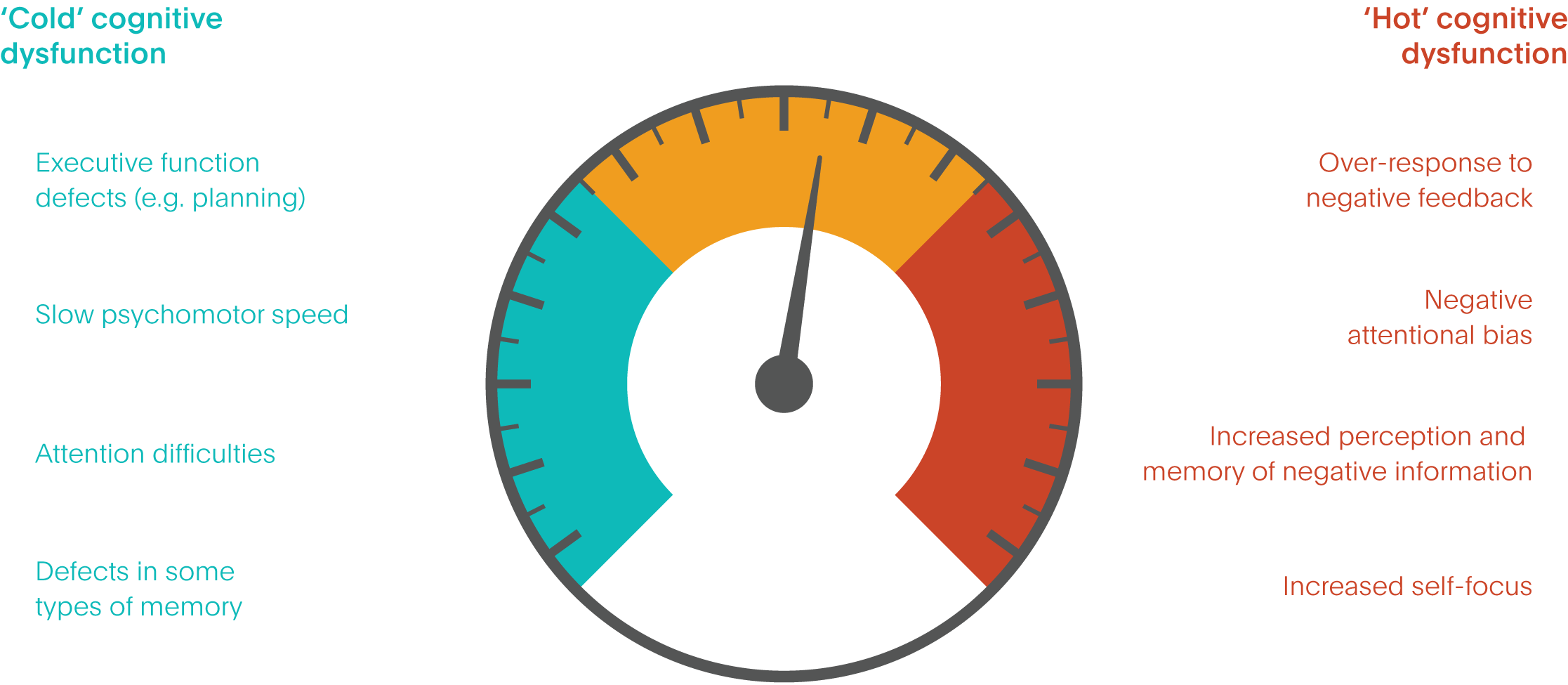

Depression is associated with dysfunction in ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ cognition, and both have important functional consequences in depression.1 These ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ elements of cognition are not independent. For example, heightened responses to negative feedback in patients with depression can impair their performance on ‘cold’ cognitive tasks.1

Hot and cold cognitive symptoms in major depressive disorder1-3

“Many clinicians will identify ‘hot’ cognitions (associated with emotions) in depression, such as shame, anxiety and guilt, but are less likely to identify ‘cold’ cognitive dysfunction. Clinicians are more likely to identify daily functional difficulties, the cause of which may be unrecognised ‘cold’ cognitive dysfunction.”

Harry Barry

Demonstrating negative bias

Negative bias can be demonstrated by a range of different measures. These can include memory for negative and positive information or the interpretation of, and speed to respond to, negative and positive cues. For example, depressed patients are more likely to remember negative information, to interpret ambiguous information as negative and to pay greater attention to aversive or threatening information.4

Mapping cognitive dysfunction

Negative bias in depression is associated with a failure of top-down control by the prefrontal cortex over the amygdala.5 For example, in one study, patients with depression showed less dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and less right amygdala deactivation than control individuals.6 ‘Cold’ cognitive defects have also been mapped to various brain regions including parts of the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. For example, a number of studies have shown that tests of executive function, including decision-making ability, activate a neural network that includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7-9